.jpeg)

Reproduction of a painting by Rustem Eminov depicting the deportation of Crimean Tatars

The forced passportization of Crimeans, which the Russians resorted to in the first weeks of the occupation, was called the restoration of serfdom. It was possible to refuse a Russian passport - but only in theory. In reality, it meant giving up all rights, including property rights. Eleven years later, the inventive invaders have found another way to punish Ukrainians with Russian citizenship — this time by revoking it.

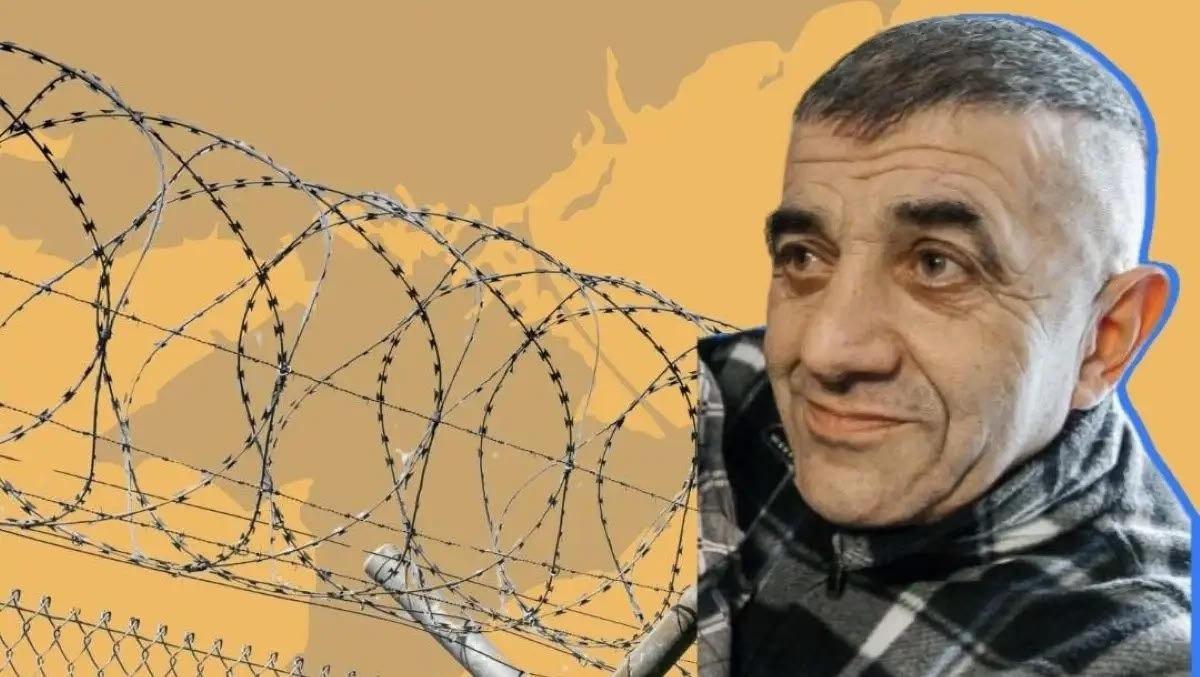

The new method is being tested on Crimean Tatar political prisoners. At present, at least five Crimeans have been declared unworthy of Russian passports. Four of them were convicted in the Hizb ut-Tahrir case: Ekrem Mamedov, Lenur Seydametov, Nasrulla Seydaliev, and Marlen Mustafayev.

The fifth person stripped of Russian citizenship is Nariman Derman, a 58-year-old resident of the newly occupied Novoalekseevka in the Kherson region. Despite his disability due to epilepsy, the Crimean was thrown behind bars for three and a half years: he was punished for participating in the blockade of the peninsula in 2016 as part of the Noman Chelebidzhihan battalion.

What does this mean for prisoners? Upon completion of their prison terms, they will be prohibited from returning to Crimea. Along with them, their families will obviously be forced to leave the peninsula. This indicates that Russia is currently implementing a plan to expel disloyal populations from its territories. Some call this “hybrid deportation.” However, it is not.

This definition applies to the before the great war departure of tens of thousands of Ukrainian citizens from Crimea and the occupied part of Donbas who did not accept the occupation In fact, conditions were created in which it was dangerous for people to remain in their homeland, but formally they left of their own free will.

Now there is no “hybridity.” On the contrary, we are talking about the most brutal form of genocide, where forced departure from the homeland is preceded by years of imprisonment and torture. In this, Putin's regime has already surpassed Stalin and Hitler. Because those two used either deportation or prison. The modern descendant of these two historical executioners combines all forms of abuse at once.

Legally, Russia revokes acquired citizenship for serious criminal offenses such as “terrorism,” “espionage,” and “treason.” However, the cases involving Crimeans do not even comply with repressive Russian legislation. After all, they were forcibly declared citizens of Russia by federal law on March 21, 2014. According to this document, all residents of Crimea registered on the peninsula on the day of the so-called referendum were automatically recognized as citizens of Russia. That is why Moscow considered director Oleg Sentsov and members of the Mejlis Eskender Bariyev and Abmedjit Suleimanov, who had never even held Russian passports in their hands, to be its citizens.

However, no one in the current Russian Federation pays any attention to this legal conflict. Human rights activists surveyed by CEMAAT consider two versions of why Russia began to deprive Crimeans of their citizenship. The optimistic version is that Moscow is allegedly preparing for a large exchange after the end of hostilities and is thus “cleansing” itself of legal ties with those it no longer wants to see on its territory. However, Russia did not strip the few Crimean political prisoners it has released over the past 12 years of their imposed citizenship. This was the case with Kolchenko, Dzhelal, Leniye Umerova, and even more so with its own opposition figures Yashin, Kara-Murza, and Pivovarov, whom Moscow handed over to Germany without revoking their passports.

Therefore, the second version is most likely to be realized. The pessimistic one. The occupiers are purging Crimea and other territories of Ukraine captured since 2014 of “unreliable” residents.

Human rights activists predict that after several legally formalized decisions, the occupiers will put an end to citizenship on a mass scale. Such a “simplification” has already happened with the procedure for declaring disobedient Russians as foreign agents. Whereas previously the Russian Ministry of Justice needed evidence of a citizen being financed from abroad, now it is enough for a candidate for foreign agent status to simply appear on a media platform in another country. It is likely that in the near future it will be possible to deprive people of their citizenship and deport them even without the involvement of Russian courts, as was the case in the USSR in the 1940s.