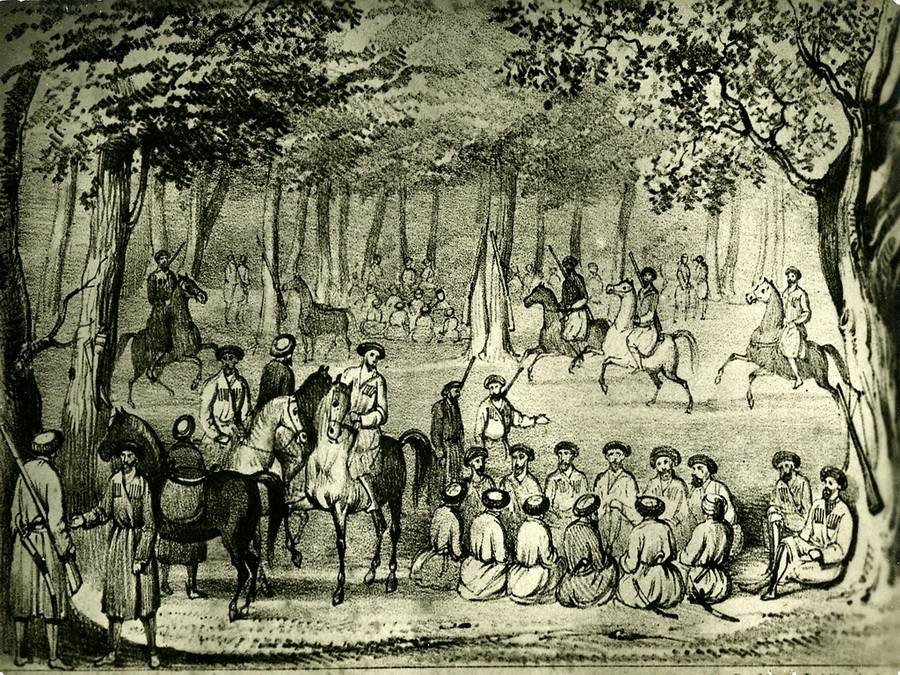

Photo caption: Tevfik Esenç, the last speaker of the Ubykh language.

Tevfik Esenç is considered the last Ubykh capable of speaking the Ubykh language. His story became widely known thanks to the novel The Last of the Departed by Abkhazian writer Bagrat Shinkuba. In the 1980s, this novel was a staple in many Crimean Tatar households; amid the forced silencing of the Crimean Tatar genocide, it told the story of another nation with a strikingly similar fate.

Recently, Vitaliy Portnikov recalled the "last Ubykh" to remind Ukrainians of how Russians destroyed subjugated nations and how many more languages might reach the same "last speaker" status—those for whom no novels will ever be written. The book about the Ubykhs is structured as an interview in which the last Ubykh recalls the stories of his grandparents, detailing the fate of one of the Caucasus's most martial peoples following their defeat in the Caucasian War.

Indeed, the Russians considered the Ubykhs more dangerous than the Chechens, who were stereotypically dubbed the "fiercest warriors of the North Caucasus." Even neighboring kindred peoples—the Abkhaz, Abazins, and Adyghes—feared them. In battle, they never surrendered, fighting to the bitter end. Ubykh territories encompassed the mountains and coastline near modern-day Sochi and Adler. At the time of the Russian conquest, the Ubykhs were considered Muslims, yet they still worshipped the ancient pagan goddess Bythwa, personified by a stone eagle in a grotto on the Black Sea coast.

In 1864, Moscow presented the subjugated Ubykhs with an ultimatum: either deportation to the inland territories of Kuban—far from the sea and the Turkish border—under Russian rule, or exile to the Ottoman Empire. The Ubykhs reportedly consulted Bythwa, and one of the elders interpreted the movement of the stone idol’s eyes as a blessing to go into exile rather than live under the "White Tsar." However, on the night the Ubykhs began gathering at the pier to board Turkish vessels and leave their homeland forever, the goddess's grotto collapsed. Some Ubykhs viewed this as Bythwa’s curse for their betrayal...

Recently, on Instagram, I found the grandson of the "last Ubykh." His name is Burak Esenç. He is an ordinary, modern young Turk. Nevertheless, he identifies as Ubykh and says that Ubykh self-awareness has recently begun gaining popularity among Turks exploring their roots. When they were driven from their homeland, about 30,000 Ubykhs reached Turkey alive. Today, Ubykh identity is claimed by no more than 1,500–2,000 people, yet only thirty years ago, that number was effectively zero.

The Ubykh language has been documented and recorded; if there is a will, it can be revived. Burak Esenç notes that since the Ubykhs in Turkey do not live in concentrated communities, he has no illusions about a linguistic linguistic restoration. However, people who are gradually discovering their Ubykh identity are becoming more active, participating in Circassian events and joining forces with them.

This has become a political issue. Every year on May 21st, the Circassians of Turkey commemorate the Russian genocide of 1864, after which they were left as a minority in their own lands. Circassian protests are becoming increasingly large-scale. Turkish Circassians clearly understand Russian policy in the Caucasus, which attempts to pit Ossetians against Ingush, Kabardians against Balkars, and Abkhazians against Georgians. Within the Turkish diaspora, representatives of these peoples stand together. The recent start of reconciliation between Armenians and Azerbaijanis is also seen by Circassians as a glimmer of hope for the revival of the Caucasus.

After all, names like Novorossiysk and Krasnodar—which even we in Ukraine often view as natural Southern Russian names—are actually occupational toponyms. Each has an indigenous Circassian name, though only Sochi and Adler have survived in common usage. They should remind us not only of Putin’s residence (where, notably, he has hosted Erdoğan 15 times) but of a territory that is occupied—just like Crimea or Donetsk.